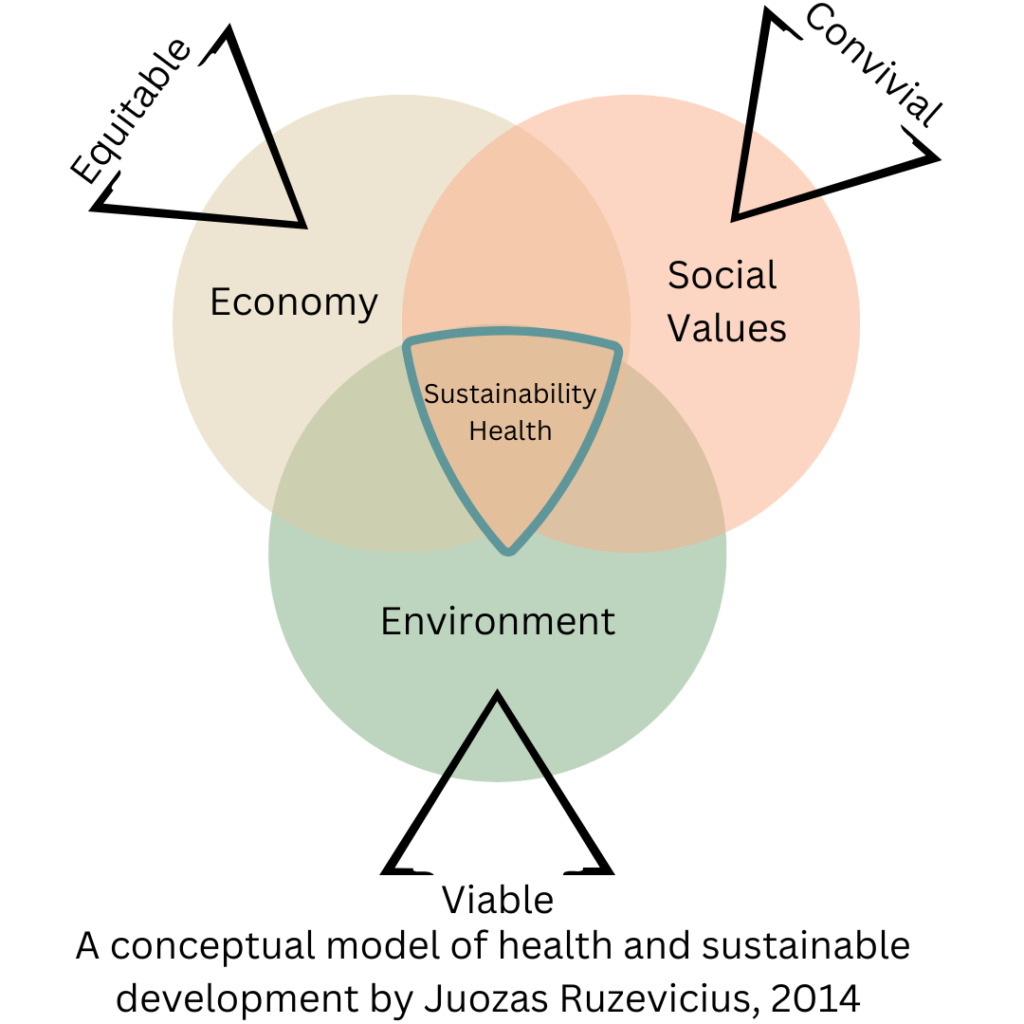

There is an intrinsic link between health and sustainability, as both influence each other.

For the UN, health and wellbeing are part of the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals, expressed as such: “Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages.” That is because, according to them, “healthy people are the foundation for healthy economies”. Nevertheless, going beyond economies, the health of both the environment and people will allow harmonious, inclusive and prosperous societies.

Wanyenze et al. (2023) defined ‘sustainable health’ as ‘a multisectoral area for study, research, and practice towards improving health and well-being for all, while staying within planetary boundaries’.

Cavendish Living Lab - Health & Wellbeing

With a focus on hydroponics, the Lab is also interested in the health benefits of such systems. For example, the sound of running water can relax people. Indeed, elements of nature seem to impact our wellbeing, often in positive ways (i.e. Michels & Hamers, 2023). Studies showed that water sounds have restorative effects in young adults, translating into a decrease in individuals’ heart rates from anxiety status and healthy autonomic nervous activity (Hsieh, Yang, Huang & Chin, 2023; Hsieh & Yang, 2022). Other physiological responses to water sounds are systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure and respiratory rate, and cortisol recovery (Zhu et al., 2024). There are still some inconsistencies in the results of studies in this field and a more comprehensive understanding is needed (i.e. Lee et al., 2022; Aletta, Oberman & Kang, 2018; Kang et al., 2016). However, water sounds’ impact on health has a great positive potential.

Cavendish Living Lab focuses on raising awareness about the correlation between our health and our environment through presentations, events, and workshops. By improving ourselves, we can improve our environment as we become more aware of our impact, more creative and innovative in a non-invasive way. For example, Aqil (2014) suggested that humans depend on the natural environment not only for material needs like food and water but also for their psychological, spiritual, and emotional well-being. There are many shared objectives between sustainability and mental health promotion, so health advocates should be involved in protecting and promoting the natural environment, as well as practices like mindfulness that can enhance flourishing and sustainability (ibid).

Similarly, in 2020, the World Happiness Report issued a paper showing that countries with higher scores on the SDG Index seem to have improved subjective well-being (SWB), For example, the Nordic countries rank the highest in both rankings. A highly significant correlation coefficient of 0.79 between the SDG Index and SWB scores indicates the importance of a holistic approach to economic development for improving citizen well-being. The relationship between the SDG Index and SWB takes a quadratic form, suggesting that a higher SDG Index score correlates more strongly with higher SWB at higher levels of the SDG Index. This implies that economic growth is a significant driver of well-being at the early stages but becomes less important later in the development cycle. In other words, there are increasing marginal returns to sustainable development concerning human well-being. Nevertheless, thorough research may uncover some conflicts where sustainability efforts require people to alter their habits, which could result in a decline in their well-being, at least in the short term at the country level.

The CLL offers some workshops relating to mental health and sustainability. We are available on request! If you are interested, please contact us.

More background about Health and Sustainability

There is increasing international awareness among health and climate leaders, and Cop28 has recently released the first-ever declaration to place health at the heart of climate action. This declaration aims to accelerate the development of climate-resilient and sustainable health systems and reduce significant emissions across the sector.

Research shows that around 25% of total healthcare emissions come from energy consumed in manufacturing supply chains, such as those producing drugs and vaccines. Other less obvious sources include gases such as nitrous oxide, used as anaesthetics, emissions from waste disposal, and patients using inhalers that rely on carbon-based propellants. The annual carbon footprint of NHS England is estimated to be 25 million tonnes.

According to a Lancet medical journal report, climate change is identified as the most significant global health threat of the 21st century. This is due to increasing rates of long-term illnesses caused by air pollution and the rise of communities living in disaster zones as a result of global warming.

The healthcare sector is a significant contributor to greenhouse gas emissions. A report published in 2019 revealed that the healthcare industry’s overall carbon footprint is equivalent to almost twice the aviation industry’s emissions, making up 4.4% of the world’s net greenhouse gas emissions. If the healthcare sector were to be considered a country, it would rank as the fifth-largest contributor to global emissions (between Russia (4.65%) and Japan (3.47%)).

Hospitals can reduce emissions in many ways. By implementing initiatives like solar power installation, waste reduction programs, and renewable energy purchases, it’s possible to receive a positive return on investment while also reducing greenhouse gas emissions. In the near future, this could lead to more stable energy prices. And in the long run, investing in climate-friendly solutions now could save a significant amount of money by reducing the number of patients who need treatment for climate-related illnesses, such as chronic lung conditions caused by air pollution. For example, upgrading or refurbishing diagnostic imaging devices can reduce carbon emissions and the cost of ownership, according to a Phillips Healthcare research. Healthcare can also benefit from AI in reducing their emissions by precisely analyzing scans and identifying when unnecessary repeats are being performed. The latest devices such as Philips Incisive CT are designed to be more energy-efficient than their predecessors and integrate AI within the system to improve accuracy in radiation dosage and enhance image quality, thereby minimizing the frequency of repeat scans.

What practical steps can we take?

According to the King’s Fund, to achieve more environmentally sustainable practices, it is important to work on improving operational efficiency, transforming the service model to focus more on prevention and shifting care upstream, improving coordination and integration of care, and constantly focusing on maximizing value for patients. In practical terms, this means that it is crucial to develop a thorough understanding of the problem at the local level, which can be achieved by systematically measuring environmental impacts. Additionally, it is important to leverage the synergies between environmental sustainability and other organizational objectives, invest in preventive approaches to reduce the demand for formal care, and explore the benefits of new technologies such as telehealth and telecare. Finally, it is important to improve medicine management and prescribing practices to reduce the inefficient or wasteful use of pharmaceuticals.

Furthermore, the healthcare company, Bupa, underpins three fundamental principles for sustainable health.

- Sustainable prevention: Keeping individuals healthy for as long as possible and encouraging them to take an active role in their own health and wellbeing can significantly reduce the chances of them becoming ill or requiring medical treatment, thereby lowering healthcare consumption. Sustainable prevention involves focusing on primary prevention (health and lifestyle), secondary prevention (screening to identify disease in its earliest stages) and tertiary prevention (reducing the effects of established disease) to achieve both short-term and long-term sustainability benefits.

- Sustainable pathways: Simplifying access routes to healthcare services and detecting illnesses at an early stage are often associated with less resource-intensive treatment. By ensuring that people receive timely and appropriate care, and by making healthcare pathways more efficient and integrated (for example, through initiatives like digital triage and “one-stop” diagnostic clinics), healthcare’s environmental footprint can be reduced by lowering patient travel and eliminating unnecessary or duplicated tests that are common in fragmented healthcare systems.

- Sustainable practice: It is important to minimize the carbon footprint and broader environmental impacts of healthcare delivery when providing care or treatment to patients. This can be accomplished by reducing emissions or resources required to deliver high-quality health outcomes. For example, waste associated with procedures can be reduced, sustainable products/materials can be used, or equipment can be reused where clinically appropriate. To ensure that the environmental impact of care does not compromise health outcomes or quality of care, healthcare organizations and professionals should gather data that can demonstrate both the clinical effectiveness and environmental impacts of their practices.

References and Sources

Wanyenze et al. (2023). Sustainable health—a call to action, BMC Global and Public Health, 1, 3.

https://bmcglobalpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s44263-023-00007-4 –

https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/insight-and-analysis/reports/sustainable-health-social-care

https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/health/

https://www.bupa.com/news/stories-and-insights/2022/what-is-sustainable-healthcare

Helliwell, J. F., Layard, R., Sachs, J., & De Neve, J. E. (2020). World happiness report 2020.

https://worldhappiness.report/ed/2020/sustainable-development-and-human-well-being/

Aletta, F., Oberman, T., & Kang, J. (2018). Associations between positive health-related effects and soundscapes perceptual constructs: A systematic review. International journal of environmental research and public health, 15(11), 2392.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30380601/

Kang, J., Aletta, F., Gjestland, T. T., Brown, L. A., Botteldooren, D., Schulte-Fortkamp, B., … & Lavia, L. (2016). Ten questions on the soundscapes of the built environment. Building and environment, 108, 284-294.

https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/103634/1/Kang_et_al_White%20Rose_final.pdf

Hsieh, C. H., Yang, J. Y., Huang, C. W., & Chin, W. C. B. (2023). The effect of water sound level in virtual reality: A study of restorative benefits in young adults through immersive natural environments. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 88, 102012.

Hsieh, C., & Yang, J. Y. (2022). The effect of water sound level on individuals’ psychological and physiological benefits: A study of virtual reality experience on urban Forest Trail. Available at SSRN 4101162.

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4101162

Zhu, R., Yuan, L., Pan, Y., Wang, Y., Xiu, D., & Liu, W. (2024). Effects of natural sound exposure on health recovery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Science of The Total Environment, 171052.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048969724011914

Lee, J. S. L., Hosni, N., Rusli, N., & Ghani, N. A. A REVIEW OF THE PSYCHOLOGICAL EFFECT OF ENVIRONMENTAL SOUND. Management, 7(27), 282-296.

http://www.jthem.com/PDF/JTHEM-2022-27-03-22.pdf

Michels, N., & Hamers, P. (2023). Nature Sounds for Stress Recovery and Healthy Eating: A Lab Experiment Differentiating Water and Bird Sound. Environment and Behavior, 55(3), 175-205.

Aqil, Z. (2014), Sound Mental Health: Key Predictor for Ecologically Sustainable Development of Society. International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, 5(2), 132-141